The High Cost of Confusing Policies: What Adobe & Slack Can Teach Us

Aug 14, 2025

Contracts, policies, and terms of service are supposed to clarify the rules, but too often, they do the opposite. When dense legal text lands in the hands of employees, customers, or the public, it can confuse, frustrate, or even spark a PR crisis.

That’s where contract and legal design steps in, to ensure that what you intend to communicate is what your audience actually understands. The Adobe and Slack case studies prove it: when clarity is ignored, the consequences can ripple across trust, reputation, and business outcomes, but when it’s applied, the payoff is enormous.

Adobe’s Terms of Use Backlash: A Case Study in the Cost of Ambiguity

Last year, Adobe found itself in a storm of public outrage when it released its update to its terms of use. Specifically, the clauses governing Adobe’s access to user content and the ownership rights of that content were considered very problematic. When language leaves any room for doubt on these two points, anxiety spreads quickly.

For Adobe’s user base, millions of creative professionals whose livelihoods depend on intellectual property, these are not minor details. They are the very core of trust between the platform and its customers. The reaction was swift and widespread.

The controversy began when Adobe pushed a routine re-acceptance of updated terms to its Creative Cloud and Document Cloud customers. Social media quickly lit up with claims that Adobe had given itself complete access to user content, or worse, the ability to steal or train AI on their work without permission.

Adobe found itself at the center of user outrage after the latest update to its Terms of Use left many customers fearing the company had broad, unchecked access to their creative work. For Adobe’s core audience, designers, photographers, videographers, two issues stood out as especially critical: uncertainty over the extent of Adobe’s access to their content (section 2) and ambiguity around ownership rights (Section 4).

When Legal Ambiguity Becomes a Business and PR Problem

Adobe’s CEO, Scott Belsky, admitted much of the uproar could have been avoided if the company had communicated more precisely from the outset. “People were justifiably concerned,” Belsky acknowledged, stressing that fears about Adobe stealing work or training its AI models on customer content were unfounded.

As Adobe CEO Belsky noted in a thread on X:

“While the team addresses your legal questions, I can clearly state that Adobe does NOT train any GenAI models on customer’s content… there are probably circumstances… where the company’s terms of service allow for some degree of access.”

The word “probably” stood out for the Adobe community of users, which only added more oil to the fire. It raised more questions from users about whether Adobe itself had fully mapped all possible access scenarios. If a company of Adobe’s scale can’t clearly articulate its boundaries, it’s a signal that clarity in contracts is not just a legal discipline, it’s a governance and trust imperative.

Adobe did share a redlined version of the changes in its public communication, a welcome step toward transparency. But that alone wasn’t enough. The underlying terms still contained problematic language, and what customers needed was not just visibility of the edits, but actual fixes to the terms themselves.

In Adobe’s case, the updated terms lacked the structure, transparency and clarity, that could have prevented panic all over the internet. The irony is that the backlash also gave Adobe an opportunity: To restate its commitments, to clarify its terms language, and to demonstrate transparency by acknowledging mistakes.

Less than two weeks later, responding to user pressure, Adobe released updated Terms of Use featuring clearer language, new explainer texts, and even a short explainer video from the Adobe legal team.

From Cluttered Legalese to Clear Structure

A closer look at the changes reveals more than just plain-language editing, it’s a complete reorganization of key clauses that really mattered to users. Let's analyze how they changed from the original version to the updated one.

Old definition of “Content” (excerpt from Section 4.1):

“‘Content’ means any text, information, communication, or material, such as audio files, video files, electronic documents, or images, that you upload, import into, embed for use by, or create using the Services and Software. We reserve the right (but do not have the obligation) to remove Content or restrict access… We do not review all Content… but we may use available technologies… to screen for certain types of illegal content…”

This was a long, glued-together clause mixing definitions with policy, process, and enforcement, confusing at best, intimidating at worst. Instead of breaking the provision into discrete, digestible points, it’s one long block that defines “Content,” states rights, disclaimers, and exceptions all in a single breath. Readers have to hold multiple concepts in working memory at once, definition, rights, obligations, limitations, making it harder to process accurately. The brain tends to skim, skip, or make quick (and often wrong) assumptions just to cope with the overload. Phrases like “we reserve the right (but do not have the obligation)” or “we do not review… but we may use technologies to screen” create ambiguity. The net result? Readers walk away with an incomplete or incorrect understanding, exactly the opposite of what a legal agreement should achieve. In user terms, it’s like being told “Don’t worry, we won’t look at your stuff… unless we do.” That breeds suspicion rather than clarity.

New definition of “Content” (Section 4.1):

“Content” means any text, information, communication, or material, such as audio files, video files, electronic documents, or images, that you upload, import into, embed for use by, or create using the Services and Software.

The revised definition of “Content” is much cleaner than the earlier, all-in-one clause. It focuses solely on what counts as Content, without mixing in rules, rights, or obligations. That’s a major improvement because it keeps scope and rights separate. It tells you what’s in the bucket labeled “Content” without immediately jumping into how it will be handled or governed. That clarity makes later clauses easier to read. It uses relatable examples, like listing “audio files, video files, electronic documents, or images” gives the reader something concrete to latch onto, instead of leaving it abstract. That said, while the definition itself is straightforward, the real shift is what comes after, the reorganization of how users access, interact with, and control their Content. That’s where the real implications for usability and trust show up, and that’s what we’ll analyze next.

The Big Shift on “Adobe’s Access to Your Content”

The same reorganization happened with the issue of content access. Before the update on the updated terms (excuse the pun!), Adobe said it may “access, view, or listen to your Content (defined in section 4.1 (Content) below) through both automated and manual methods, but only in limited ways, and only as permitted by law.” Adobe continued: “For example, in order to provide the Services and Software, we may need to access, view, or listen to your Content to (A) respond to Feedback or support requests; (B) detect, prevent, or otherwise address fraud, security, legal, or technical issues; and (C) enforce the Terms, as further set forth in Section 4.1 below. Our automated systems may analyze your Content and Creative Cloud Customer Fonts (defined in section 3.10 (Creative Cloud Customer Fonts) below) using techniques such as machine learning in order to improve our Services and Software and the user experience. Information on how Adobe uses machine learning can be found here: http://www.adobe.com/go/machine_learning.”

That clause was essentially a dense and cluttered list of operational rights, wrapped in legal qualifiers. The result: users saw only that Adobe “may access, view, or listen to” their content, and quickly assumed the worst. The structure offered no visual hierarchy to distinguish routine operational needs from exceptional circumstances or prohibitions.

The new version, Section 2.2 “Our Access to Your Content” breaks this into clearly labeled subsections (A–G), covering operational use, scanning limits, illegal content detection, analytics opt-outs, and AI training restrictions. From a cognitive perspective, the shift from a linear paragraph to a chunked, list-based format drastically reduces mental load, making it easier for users to locate and understand specific rules.

This structured breakdown is easier to follow and gives users a much more transparent map of when, how, and why Adobe might access their work. The new clause embraces a categorical breakdown, giving each type of access its own labeled subsection (A) through (G). This mirrors information architecture best practices in contract design:

-

Scoping first: Beginning with “No one but you owns your content” sets a reassuring baseline before introducing exceptions.

-

Negative commitments: Explicit “Here’s what we don’t do” language works as a trust signal, something almost entirely absent in the old version.

-

Separation of local vs. cloud content: This distinction matters enormously to users but was buried in the previous text.

-

Clear opt-out rights for cloud content: By pointing to external FAQs and giving users agency, the new clause shifts from a unilateral rights statement to a collaborative terms framework.

The numbered list in Adobe’s new Section 2.2 is already a huge leap forward, it breaks down information into clear, digestible chunks instead of burying it in one impenetrable paragraph. Numbering not only helps readers follow the logic step-by-step but also makes it easier to reference specific points when discussing or negotiating the terms.

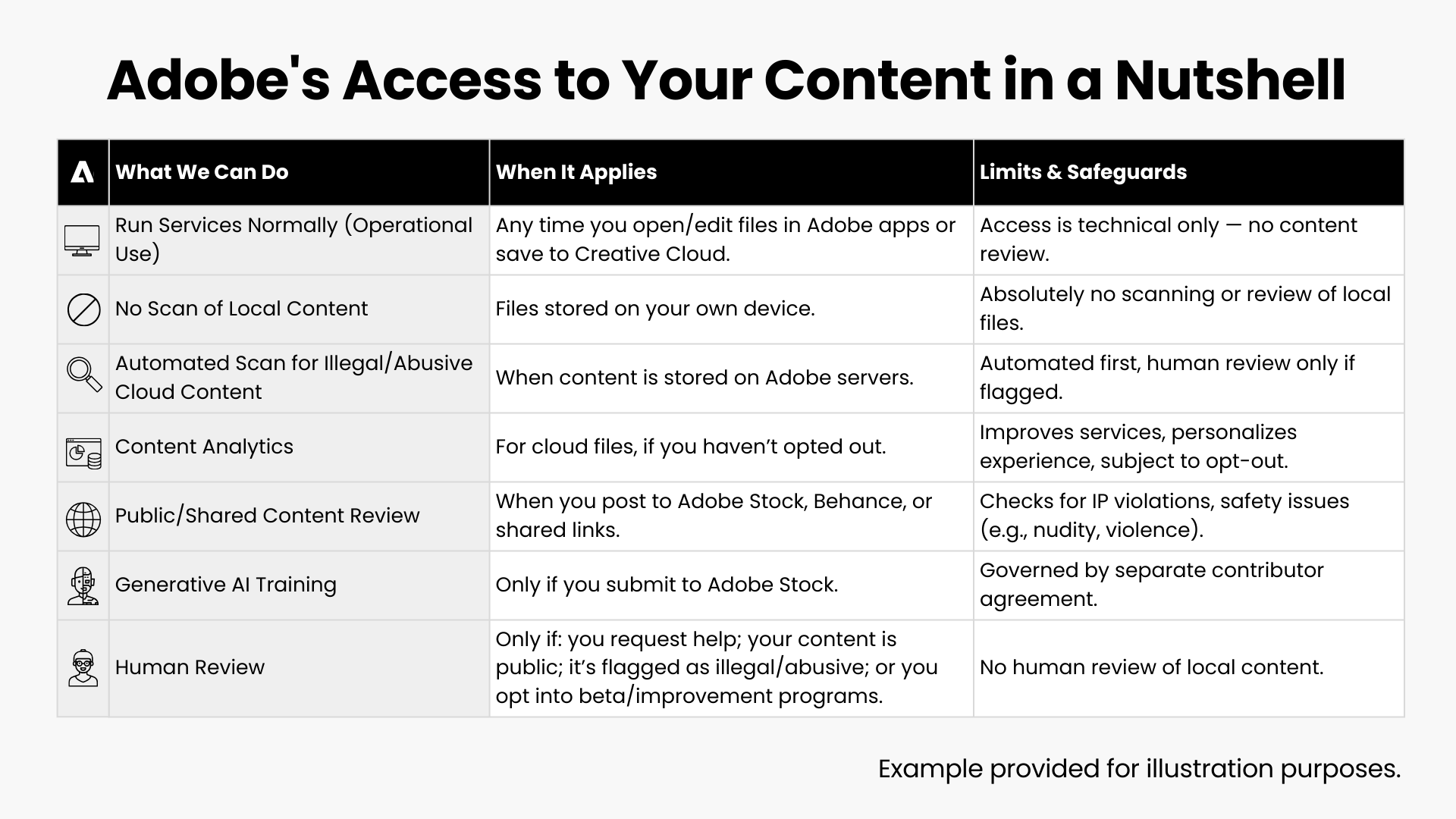

Still, Section 2.2 could have gone even further. Imagine pairing that plain-language summary with a visual matrix that organizes the content into three clear columns: (1) What We Can Do; (2) When It Applies; (3) Limits & Safeguards.

Here’s a proposed visual fix: an “In a nutshell” table that distills the section into a quick, scannable format. This could act as a supplement to the full text, or even as a replacement, provided the table’s content is complete and accurate. By combining structured text with a visual summary, Adobe could have delivered a level of clarity that not only informs but also reassures users.

Privacy Settings and the Default “Opt-In” Controversy

The backlash didn’t end with the Terms rewrite. The debate spilled into creative and design blogs, where writers tried to explain what the terms changes meant for professionals, and, in the process, many turned their attention to Adobe’s privacy policy.

Adobe’s “Content Analysis” setting comes enabled by default, meaning users must actively go into their Data and Privacy settings to turn it off. This type of “opt-in by default” design is widely criticized in UX and ethics circles because it nudges users into agreeing without explicit consent, eroding trust. In many jurisdictions, such patterns are considered deceptive and, in some cases, legally prohibited, since true consent must be freely given, informed, and unambiguous.

One key finding: in theory, users can prevent their content from being analyzed entirely by avoiding Creative Cloud storage, since Adobe only analyzes content processed or stored on its servers. In practice, however, this is much more difficult, as many features, particularly AI-powered tools, depend on Adobe’s servers to function, limiting the effectiveness of this workaround.

The real takeaway? Adobe's episode wasn’t about a hidden plan to steal work. It was about the consequences of unclear terms, and how quickly ambiguity can turn into outrage, eroding trust that took decades to build. Lack of clarity in terms can quickly erode trust when public sentiment turns against a company.

Slack’s AI Data Training Backlash: When Format Fails Function

Last year Slack also faced significant public backlash over its AI training practices. Slack had quietly introduced an AI training policy that automatically opted all users into having their data used to train AI models. It faced its own wave of public backlash, not because its policy was inherently reckless, but because it was extremely confusing.

The controversy centered on Slack’s default approach of using user-generated content, including messages and files, to train its AI models unless users actively opted out. While Slack clarified that it does not use customer data to develop large language models (LLMs) or share it with third parties, the initial policy exposed the company to criticism regarding transparency, consent, and user control.

The policy text was, allegedly, privacy-conscious. But in practice, the opt-out process was buried in the fine print and required emailing Slack’s customer support, an outdated, friction-heavy step. Additionally, there was no clear indication of what data was actually included in AI training and unclear separation between platform-level machine learning (which could help improve Slack’s search or recommendations) and generative AI models (which raised bigger questions about proprietary data).

The Opt-In-by-Default Problem

When word spread of the change, the reaction was immediate and intense. Slack’s “opt-in by default” approach was interpreted by many as putting the company’s AI ambitions ahead of its customers’ privacy rights. This perception was especially damaging given Slack’s role in hosting sensitive corporate communications, including confidential strategy discussions, HR matters, and financial planning. The idea that this data might be used to train AI models triggered a flood of opt-out requests and a noticeable uptick in chatter about switching to competing platforms.

Clarifying After the Firestorm

Under mounting pressure, Slack responded with two key communications:

-

An update to its Privacy Principles, making its stance on data use for AI more explicit.

-

A detailed engineering blog post, breaking down the architecture and data boundaries of its AI features.

From these clarifications, customers learned that:

-

Generative AI models are hosted on Slack’s own infrastructure.

-

No customer data is used to train large language models.

-

AI features like summarization or recommendations rely only on relevant, permissioned data, and stay within the scope of a customer’s own Slack workspace.

The Missed Opportunity: Using Visuals to Increase Transparency and Build Trust

This episode wasn’t primarily about bad policy, it was about bad presentation. A single, well-designed policy could have shown:

-

What types of data are used for each function.

-

Exactly how (and where) users could control their participation.

Here’s how it could have been made instantly clearer - The Visual Fix:

With this matrix, users would instantly see: (1) What’s being used; (2) How it’s being used; (3) Where they can control it. This is good AI vs. controversial AI, clearly separated for the public eye.

The Slack case is a reminder that in an age of AI anxiety, clarity isn’t a luxury, it’s a trust-building necessity. Simple visuals in the forms of tables, companies can surface the assurances people care about most, before misinformation takes root. Instead, most of legal information remained buried in text-heavy legal sections, creating fertile ground for misinterpretation and suspicion.

Final Takeaways: The Cost of Confusion vs. the Value of Clarity

The moral of the story is simple yet powerful: how you communicate is as important as what you communicate. Adobe and Slack’s episodes are more than isolated PR hiccups, they’re case studies in how ambiguity, even when unintended, can erode trust at scale. When policies leave room for doubt, the vacuum gets filled with speculation. Speculation turns into suspicion. Suspicion snowballs into backlash. And suddenly, what could have been a minor clarification becomes a prolonged reputational and business risk.

This isn’t just a “legal” problem, it’s a business and PR problem. The very same policy, expressed with precision, structure, and clarity, could have been met with calm rather than panic. That’s where contract and legal design come in: they bridge the gap between the drafter’s intent and the reader’s understanding.

What’s “clear” in the mind of the policy author is often not clear to the audience reading it. Legal design turns that gap into alignment, transforming intentions into true comprehension through structured organization, plain language, and purposeful visuals. The result? Not only fewer misunderstandings, but also more trust, more user agency, and more resilience in moments of public scrutiny.

And here’s the kicker: it doesn’t take weeks of work or a legal department overhaul. With a methodical, strategic process, you can restructure and present policies in a way that preserves legal integrity while dramatically improving usability. You can realistic do it in less than 3 months or even than 2 weeks, like Adobe did!

If you want to master these skills for yourself or equip your team to do the same, we invite you to join our Contract and Legal Design Certification program here. After all, in today’s world, how you communicate is as critical as what you communicate, and legal design ensures that both are working in perfect harmony.

In today’s world, where AI, data privacy, and platform policies are under a magnifying glass, clarity isn’t optional. It’s the competitive edge and an operational advantage. Legal design makes sure that what you mean and what people hear are the same thing, keeping your business out of unnecessary storms and your users on your side.